A History and Psychology of Automatic Writing

The Hand That Writes

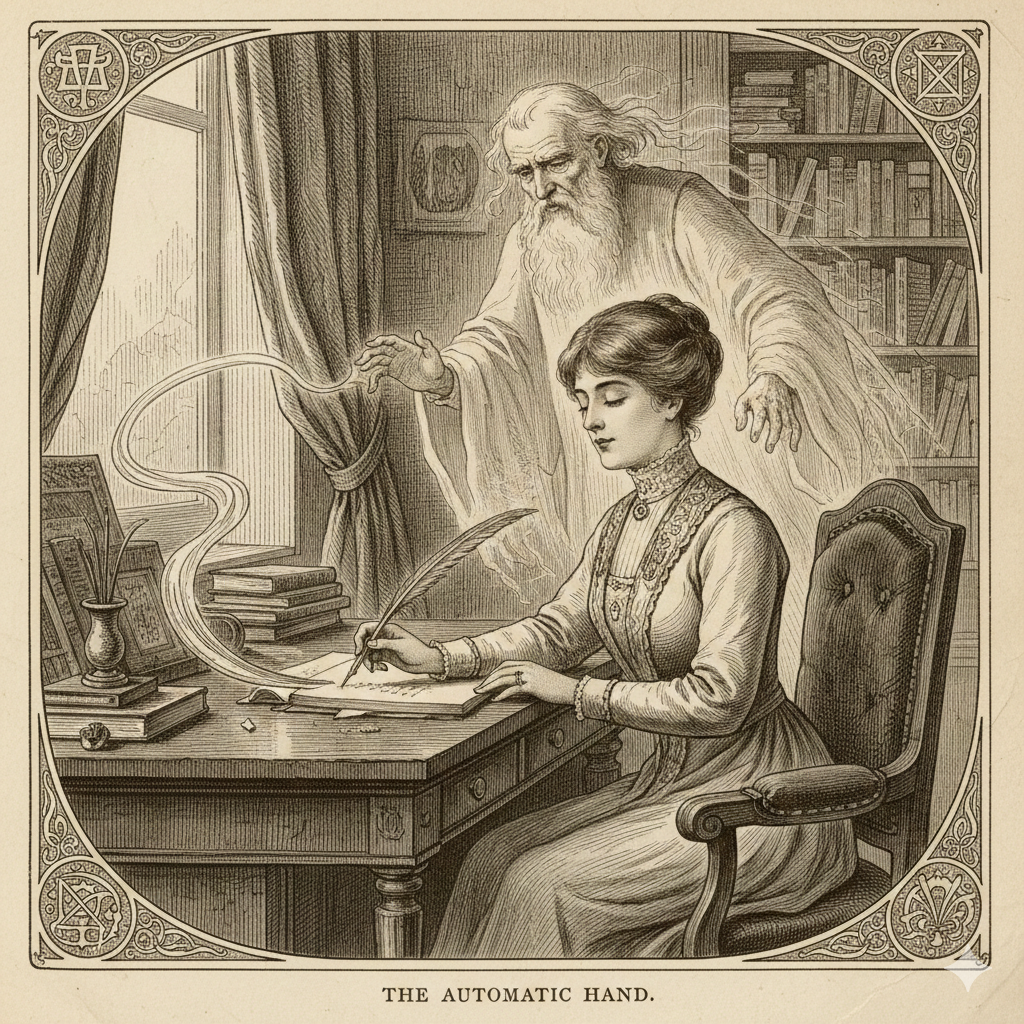

A pen rests on paper. The room is quiet. The writer claims not to know what will come next. Words begin to form, slowly at first, then in a rushing stream. When the page is filled, the writer looks down and reads what “someone else” has written. For some, this is a parlour curiosity from the age of séances. For others, it is sacred communication, proof that the boundary between the living and the dead is porous. For psychologists, it is a window into the divided architecture of the mind. The practice is known as automatic writing.

Automatic writing, sometimes called psychography, sits at a curious threshold between belief and cognition. It has roots in nineteenth century Spiritualism, flourished in drawing rooms lit by gas lamps, and later migrated into the avant garde studios of Surrealist artists. It has been tested in laboratories, defended in memoirs, and quietly practised at kitchen tables. To understand it is to explore not only a mediumistic tradition, but also the strange ways in which consciousness can step aside and allow another voice to emerge.

Origins in the Age of Spiritualism

Modern automatic writing took shape in the mid nineteenth century, during the rise of Spiritualism in Britain and the United States. In 1848, the Fox sisters of Hydesville, New York, claimed to communicate with spirits through raps and knocks, igniting a movement that spread rapidly across the Atlantic[1]. Table turning, spirit photography, and trance speaking became common features of Victorian séances. Writing, however, offered something more tangible. It produced a document.

By the 1850s and 1860s, mediums reported that spirits could guide the hand directly. Instead of raps spelling out letters, the pen itself moved under unseen influence. The practice was often framed as passive. The medium relaxed, sometimes entering a trance, and allowed the hand to write without conscious intention. The resulting text might be a letter from a deceased relative, a moral exhortation, or a complex theological discourse.

The Society for Psychical Research, founded in London in 1882, took a serious interest in such phenomena[2]. Rather than dismissing automatic writing outright, investigators collected scripts, analysed handwriting, and interviewed participants. Their work did not prove spirit agency, but it preserved detailed records that remain invaluable for historians. Automatic writing was no longer only a drawing room curiosity. It had entered the archive.

Case Study: Hélène Smith and the Martian Scripts

One of the most famous cases of automatic writing emerged in Geneva at the end of the nineteenth century. Catherine Élise Müller, better known under the pseudonym Hélène Smith, became the subject of study by psychologist Théodore Flournoy. During séances, Smith produced elaborate automatic texts that she claimed were communications from past lives and even from inhabitants of Mars.

Flournoy documented these sessions in his 1900 study From India to the Planet Mars[3]. Smith’s hand produced flowing scripts in an invented “Martian” language, complete with grammar and vocabulary. For believers, this was evidence of otherworldly contact. For Flournoy, it demonstrated the creative powers of the subconscious. He argued that Smith’s productions drew upon memories, fantasies, and cultural influences, woven together outside her conscious awareness.

The case remains instructive. It shows both the richness of automatic writing and the difficulty of interpretation. Smith was not simply scribbling random marks. She generated coherent narratives and linguistic systems. Whether one sees spirits or psychology at work, the phenomenon demands explanation.

The Psychology of Divided Consciousness

Automatic writing has long been associated with dissociation, the capacity of the mind to split processes that are normally integrated. William James, writing in The Principles of Psychology, described cases in which individuals produced writing while claiming no conscious control[4]. He treated such episodes not as supernatural proof, but as evidence that consciousness is layered and permeable.

Modern psychology often approaches automatic writing through the lens of ideomotor action. The ideomotor effect, discussed in contemporary psychological literature, refers to movements initiated unconsciously in response to ideas or expectations[5]. The same mechanism is commonly invoked to explain the movement of Ouija boards or dowsing rods. Subtle muscular activity, guided by belief or suggestion, can produce meaningful patterns without deliberate intent.

Neuroscientific studies of agency also complicate the picture. Research into the sense of authorship suggests that the feeling of controlling an action can be disrupted under certain conditions[6]. When prediction and feedback misalign, individuals may experience their own movements as alien. In automatic writing, the act may be self generated, yet subjectively attributed to another source.

This does not reduce the experience to fraud or delusion. It suggests that the human mind is capable of generating coherent material outside the spotlight of reflective awareness. The writer genuinely feels surprised by the text because the cognitive processes that shaped it operated beneath conscious narration.

Automatic Writing and Creative Experiment

In the twentieth century, automatic writing found a new home in art rather than séance. The Surrealists, led by André Breton, embraced écriture automatique as a method for bypassing rational censorship[7]. Breton’s 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism called for writing “in the absence of any control exercised by reason.” The goal was not communication with the dead, but liberation of the unconscious.

Here the practice shed its explicitly spiritual frame, yet retained its core technique. The writer began with a blank page and allowed associations to unfold without editing. The result was often fragmented, dreamlike, or startlingly poetic. Surrealist automatic writing influenced literature, visual art, and later creative therapies.

This artistic adoption reveals something important. Automatic writing can function without metaphysical claims. It can be a tool for exploration, a method of discovering latent images and themes. Whether spirits are invoked or not, the act itself demonstrates that conscious intention is not the sole author of text.

Belief, Meaning, and Mediumship

Within Spiritualist communities, automatic writing remains a living practice. The Spiritualists’ National Union in the United Kingdom continues to train mediums and emphasises ethical standards in communication with the spirit world[8]. For practitioners, automatic writing is not merely a psychological curiosity. It is a pastoral act, offering comfort and perceived continuity between worlds.

Anthropologists note that mediumistic writing often reflects the cultural expectations of its setting[9]. Spirits speak the language of their time. They address contemporary anxieties. The texts reveal as much about community values as about unseen realms. In Victorian Britain, automatic scripts frequently reinforced moral order. In modern contexts, they may emphasise personal growth or healing.

The power of automatic writing, then, lies partly in narrative authority. A message that appears to come from beyond carries emotional weight. Even when psychological mechanisms are proposed, the meaning derived by participants can be profound. The page becomes a meeting point between grief, hope, and imagination.

Fraud, Scepticism, and Enduring Questions

It would be incomplete to ignore the history of exposure. Harry Houdini devoted considerable energy to debunking fraudulent mediums in the early twentieth century[10]. Some automatic writings were later revealed as conscious deception. The existence of fraud does not explain every case, but it does caution against romantic certainty.

Encyclopaedia Britannica summarises automatic writing as a form of motor automatism associated with Spiritualism, noting both its historical significance and the sceptical interpretations offered by psychologists[11]. The debate has not been settled. Instead, it has shifted focus. Rather than asking only whether spirits exist, researchers examine how belief, expectation, and cognition interact.

Even laboratory tests leave room for ambiguity. When automatic writers produce accurate information unknown to them, critics question methodology, while believers see confirmation. The phenomenon sits in a liminal space. It resists easy categorisation.

The Threshold of the Page

Automatic writing endures because it dramatizes a mystery at the heart of human experience. Who is the “I” that writes? Most of us have felt, at least once, that words arrive before we consciously select them. A phrase surfaces in the shower. A solution appears after sleep. Creative flow, described in psychological studies of optimal experience, involves a reduced sense of self monitoring[12]. Automatic writing amplifies this common condition into ritual.

In the séance room, the medium attributes the voice to spirits. In the studio, the artist calls it the unconscious. In the clinic, the psychologist studies dissociation and agency. Each framework offers part of the picture. What remains constant is the experience of otherness within the self.

The pen moves. The page fills. The writer reads and feels a flicker of estrangement, as though standing beside their own hand. Whether one interprets that moment as contact with the dead, the flowering of imagination, or the mechanics of ideomotor action, automatic writing reminds us that consciousness is not a single, solid block. It is layered, dynamic, and capable of surprising its owner.

In that sense, automatic writing is less about proving spirits than about confronting the depth of the mind. The hand that writes may belong to us, yet it gestures toward regions we do not fully command. On a quiet night, with pen poised above paper, the threshold still waits.

Works Cited

-

“Fox Sisters.” Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Overview of the 1848 events that sparked the Spiritualist movement, providing historical context for the rise of automatic writing.

Live source | Return to citation [1] -

Society for Psychical Research. Official History Page.

Details the founding and investigative aims of the SPR in 1882, documenting early research into automatic writing and related phenomena.

Live source | Return to citation [2] -

Flournoy, Théodore. From India to the Planet Mars (1900).

Classic psychological case study of Hélène Smith’s automatic scripts, analysing them as products of the subconscious imagination.

Live source | Return to citation [3] -

James, William. The Principles of Psychology (1890).

Foundational psychological text discussing automatisms and divided consciousness, relevant to early interpretations of automatic writing.

Live source | Return to citation [4] -

Wegner, Daniel M. “The Illusion of Conscious Will.” MIT Press, 2002.

Explores the ideomotor effect and the sense of agency, offering a psychological framework for understanding automatic movements.

Live source | Return to citation [5] -

Haggard, Patrick. “Sense of Agency in the Human Brain.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2017.

Reviews neuroscientific research on agency and authorship, relevant to experiences of alien control in automatic writing.

Live source | Return to citation [6] -

Breton, André. Manifesto of Surrealism (1924).

Introduced automatic writing into artistic practice, reframing it as a method of accessing the unconscious rather than spirits.

Live source | Return to citation [7] -

Spiritualists’ National Union. About Mediumship.

Contemporary organisational perspective on mediumship practice and ethical standards within modern Spiritualism.

Live source | Return to citation [8] -

Boddy, Janice. “Spirit Possession Revisited.” Annual Review of Anthropology, 1994.

Anthropological analysis of spirit communication practices, highlighting cultural framing of mediumistic experiences.

Live source | Return to citation [9] -

Houdini, Harry. A Magician Among the Spirits (1924).

Skeptical account exposing fraudulent mediumship practices, illustrating the contested history of automatic writing.

Live source | Return to citation [10] -

“Automatic Writing.” Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Concise overview of automatic writing’s definition, history, and critical interpretations.

Live source | Return to citation [11] -

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (1990).

Introduces the concept of flow states, useful for understanding altered self awareness in creative automatic writing contexts.

Live source | Return to citation [12]

0 Comments